What is the right interpretation of Witty and Jenkins (1936)?

Witty and Jenkins’ ancient study (ungated) of 63 prodigious black children is frequently cited by environmentalists and others. It’s often contended that this study provides strong evidence against the genetic hypothesis (e.g., Flynn, 1980; Brody, 1992; Lee, 2010; Nisbett, 2009). For example, in his critical review of Nisbett’s Intelligence and How to Get It, James Lee states:

[Nisbett] cites a study failing to find elevated European ancestry in a sample of gifted black children (Witty & Jenkins, 1936). Although this study does pose rather strong evidence for an environmental hypothesis, Nisbett does not mention a critical limitation: the investigators ascertained degree of white ancestry by parental self-report.(Lee, 2010. Review of intelligence and how to get it: Why schools and cultures count, R.E. Nisbett, Norton, New York, NY (2009). ISBN: 978039306505)

The study, which had two components, was a subpart of a larger study by Witty and Jenkins on intellectually superior Black children in the Chicago Public schools. Using Terman’s methodology, Jenkins was able to identify, and then study the characteristics and demographics of, 103 intellectually superior (IQ >120) children out of a population of ~8000. To address the genetic hypothesis, Witty and Jenkins looked at the relationship between genealogy and IQ for a subsample of these. Witty and Jenkins reasoned that, were the genetic hypothesis true:

In a mixed group such as we have in the United States those individuals having the largest amount of white ancestry should on the average stand higher in tests, other things being equal, than persons of total or larger amounts of Negro ancestry. (Witty & Jenkins, 1936, p. 180).

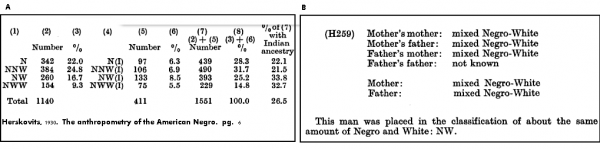

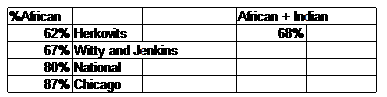

They conducted two tests of this hypothesis. In the first, they estimated the racial admixture of 63 of the children, on the basis of parent interviews — reported as N (all Negro), NNW (more Negro than white), NW (equally Negro and white), or NWW (more white than Negro) — and then compared the estimated the racial admixture to that found in a national sample of blacks by Herskovits (1930). Witty and Jenkins determined that the superior children had less white ancestry and concluded that the genetic hypothesis was falsified.

Unfortunately for their conclusion, as Mackenzie (1984) pointed out, Herskovits’ national sample wasn’t representative. The sample populations had a higher average SES and a higher average percent of white ancestry than the national black population. Interestingly in his critique of this study, Mackenzie didn’t pursue the latter issue.

Herskovits’ Ancestral data (A) and Methodology (B)

If we translate Herskovits’ ordinal ancestry data into percentages (e.g., N= 100% African; NNW=66% African, 33% Caucasian, etc.), we find that his sample had a White admixture rate of 32% (and an Amerindian admixture rate of 6%); this is compared to the current 20% admixture rate in the US Black population as reported by Zakharia et al. (2009) and to the 13% admixture rate in the Chicago Population as reported by Reed (1969). Using the same method of conversion, we see that Witty and Jenkins’ sample had a 33% admixture rate. Witty and Jenkins, of course, were right that their intellectually superior sample didn’t have a higher percent of White ancestry than Herskovits’ but both samples, nonetheless, had a higher percent than found in both the national and Chicago populations.

Witty and Jenkins’ results for their first test, thus, support the genetic hypothesis. Higher IQ African-American children were found to have a higher percent of White ancestry than both the national population and the population from which they were drawn. The comparison data set which Witty and Jenkins rely on, likewise, supports the genetic hypothesis. Hershkovits’ sample of African Americans were found to have both a higher SES, an IQ correlate, than average and a higher percent of white admixture. Research on “colorism” corroborates this finding. As I noted elsewhere:

From 1850 to the early ’1900s, US census takers were instructed to classify African Americans as Black or Mullato. They were given the following directions: “in all cases where the person is white, leave the space blank; in all cases where the person is black, insert the letter B; if mulatto, insert M” and “Be particularly careful in reporting the class Mulatto. The word is here generic, and includes quadroons, octoroons, and all persons having any perceptible trace of African blood” (Snip, 2003).

Hill (2000) found that those African-Americans classified as Mullato had a higher SES (judged by profession — e.g., white collar workers versus domestic workers) than those classified as Black and that this difference remained after controlling for social origins. Hill (2000) rejected a genetic interpretation, arguing that “[e]xplanations for a cultural or genetic origin can not be supported. Research has failed to uncover any association between white ancestry and intellectual ability among African Americans” and citing Scarr et al.; yet, as we noted above, those studies were inconclusive.

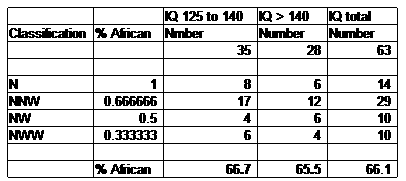

In the second test, Witty and Jenkins took a gifted (IQ > 140) subset of the 63 children and compared the average ancestry of the subset to that of the larger group (IQ = 125-140). They found no average difference in ancestry and concluded, again, that the genetic hypothesis was falsified.

On problem with their methodology was that they compared the gifted subset (>140) with the larger group (>125) instead of, more properly given the small sample size, with the non-gifted subset (125 to 140). When the proper comparison is made there is a slight, but nonetheless, non-significant difference as shown in the figure below.

Witty and Jenkins results’ for their second test, thus, support the environmental hypothesis.

How strongly, though? To put this question otherwise: what difference in admixture would the genetic hypothesis have predicted — 2%, 5%, 10%, 20%? It’s not at all clear. To answer this, one would have to know the predicted correlation between IQ and individual ancestry for this population (or even the African American population in general), yet no one has ever bothered to estimate that until Kirkegaard et al (2019) and Lasker et al (2019)'s landmark studies.

Whatever the case, taking both tests together, the findings turn out to provide at least as much evidence for the genetic hypothesis as against it. This is not, of course, how the findings are presented by proponents of the environmentalism. We may also note that Meng Hu found in 2013 that self-reported white (European) ancestry in a large sample of American blacks (NLSY79) does indeed relate to IQ, and with a positive Jensen coefficient -- as per Spearman's hypothesis.

References

- Jenkins, 1934. A Socio – Psychological Study of Negro Children of Superior

- Herskovits, 1930. The anthropometry of the American Negro

- Mackenzie, 1984. Explaining race differences: in IQ The Logic, the Methodology, and the Evidence

- Reed, 1969. Caucasian Genes in American Negroes

- Witty and Jenkins, 1936. Intra-Race Testing and Negro Intelligence

- Zakharia, et al., 2009. Characterizing the admixed African ancestry of African Americans

- Kirkegaard et al, 2019. Biogeographic Ancestry, Cognitive Ability and Socioeconomic Outcomes

- Lasker et al, 2019. Global Ancestry and Cognitive Ability